Water & Sanitation

Founded with a close friend at Harvard Medical School, this initiative installs low-cost systems to deliver clean drinking water to rural communities. The goal was to provide immediate relief, pending more elaborate solutions. Asebi, a small community in Ghana’s Eastern Region, was selected by Elorm for a first project. It had come to our attention that the main source of usable water for the community, both people and livestock, was a muddy pool of water teaming with frogs and snakes.

We had gone in with the intention of digging a well. However, we soon learnt that the community sat on a saltwater table. This meant that any water we struck would be unsuitable for everyday use unless extensive and thus expensive purification methods were also employed. After visits to the community and many conversations with locals, it was decided that we would purchase water tanks, fill them with clean water transported via water trucks a few miles away, and have residents pay an affordable amount to use the water, in order to raise funds for refilling the tanks. We concluded that by involving locals in both the decision-making and the actual implementation, the intervention was more likely to succeed in the long-term, regardless of our long-term absence in the village.

We have since shared our experience with many other nonprofits and charitable programmes in Ghana to popularise this community-led, grassroots approach to intervention.

Girl-child Education

This initiative engages underprivileged communities in conversations intended to orient them towards better practices of raising and educating children. There is a real need to move the conversation from high stakeholder forums and rountables into communities to which the conversation is most relevant. There is a need to engage directly with locals, listen to their real-life experiences, and better inform approaches.

Paanor, a village in Ghana’s Greater Accra Region, was selected for a community engagement project. Having learnt that there was not a single clinic in the community, a decision was made to engage parents, teachers, students, and community leaders in conversations about girls’ education in the sciences. And so to mark 2018’s International day for Women & Girls in Science, a team of volunteers was organised for an outreach project. The team included female doctors, Dr. Enyonam Abiti, and Dr. Ama Amaning-Darko. There were conversations with the female students as a group, in addition to one-on-one conversations with teachers, and house-to-house visits to talk to parents and community leaders. One doctor on the team shared her very inspiring story about a very humble upbringing which neither she nor her parents permitted to predetermine her future. An absolutely empowering story!

In totality, conversations with the community revealed a clear lack of motivation on the part of most of the parents to prioritise their children’s education over their participation in agriculture. This lack of motivation seemed to have infected the teachers. What is worse? The lack of motivation was understandable! For while they struggle to see a future for their children and students beyond the abysmal basic education the community could provide, there is a clear, ever-present, need to work on the family’s farms to provide sustenance. Thus, invaluable insight was gained into the interconnectedness of social and economic issues.

Community Building & Environment

With culture, tradition, and folklore that personify the Earth and preserve natural ecosystems, Ghana appears to be a fertile ground on which substantial interest in environmental welfare can be cultivated. What I sought to do with Hyde Gardens was to harness that context to create an oasis for community building. To look at sustainability in a very broad sense. One way to do that was by using the location to inspire interest in conversations on climate change, sustainability, and sanitation. An unsanctioned landfill was selected in Dzorwulu, in the Greater Accra Region, to create what would become Ghana’s first Green Museum. The area, despite how unwelcoming and unsanitary it looked, was fifteen minutes from the Kotoka International Airport.

Together with Bernard Whyte, a veteran horticulturist who serves as personal florist for Accra’s most elite, including Ghana’s current and last two presidential families, I developed the location into a place for reading, relaxing, and picnicking, where visitors, both locals and tourists, are engaged in conversations about climate change, the creative use of vegetation and horticulture to control dust and flooding in Accra, Ghana's capital, and campaign for sustainable agriculture. It seeks to offer a kind of informal, experiential education that evokes an interest in environmental issues. With educational brochures and Bernard as a resident curator, visitors are typically engaged in conversations along such lines. Hyde Gardens has also provided a very cheap location for local nonprofits to host events, helping them to engage with stakeholders, create awareness about their mission, or raise funds. It has also been a great place for upcoming photographers and artists to draw inspiration and showcase their work. Still in development, Hyde Gardens receives an average of two hundred visitors each week. Hanging out in the garden has become part of the monthly routine of some residents of Dzorwulu, Abelemkpe, and Westlands, all within walking distance of the garden. Google recently sent Hyde Gardens a congratulatory email on its 100,000th visitor.

In the long-term, I intend for the venue to usher in a new age of academic, political, and commercial explorations of the use of social amenities to promote idea flow, collaboration, and partnership, and therefore productivity and innovation. By making Hyde Gardens an organic community garden in which locals collaborate to grow vegetables for their own use, I hope to begin to create awareness about the positive impact of idea flow, collaboration, and partnership on the national economy.

Recently, inspired by an introduction to Dr. Pamina Firchow’s Reclaiming Every Peace, I have come to suspect that a community garden could be used concurrently as an inclusive tool for building peace and an “everyday indicator” for measuring it. In Dr. Firchow’s award-winning work, she argues that it is often unclear the extent to which internationally-funded intervention programmes actually impact locals, and quite often, it is quite clear that they fail to impact locals in any significant way. One must, she suggests, include locals not only in developing intervention programmes, but also, in implementing and maintaining them. She made these observations in Rwanda when hired to externally evaluate an internationally-funded peace building and reconciliation project. As she learnt, interviews and questionnaires reveal little or confusing detail on the success of interventions. So, instead, she suggests using what she calls Everyday Indicators to measure impact. Everyday Indicators are phenomena that can be measured with minimal obstacles to observation and communication.

My thinking is: a community garden is a great peace-building initiative that and supplies “everyday indicators” that could be used to measure the success of other peace-building initiatives. Firstly, a community garden is necessarily inclusive, since it heavily depends on locals to flourish. Secondly, it reveals a lot about how locals feel about their neighbours (and how they feel their neighbours feel about them) than any interview or questionnaire would. Indeed, I would argue that one ought to not only feel safe among one’s neighbours, but also, care about and feel cared about by them in order to actively contribute to a community garden from which everyone benefits. Thirdly, Everyday Indicators that could be used to measure impact may include the number, ethnicities, and level of education of contributing locals, the annual output of the garden, etc. The conclusion is that how well such an initiative does in a Rwandan community and how diverse the backgrounds of local contributors are would say a lot about if indeed peace has trickled into the world view, life experiences, and expectations of the everyday Rwandan or if the feeling of peace and security is the preserve of a privileged few (probably due to their privilege rather than to a supposed post-conflict intervention). Other indicators are conceivable. Thus, a community garden can actually be used concurrently as a tool to measure the success of peace-building efforts AND as a tool for inclusively building (further) peace. I use the phrase, "Growing Peace Locally" to describe the practice of doing so.

Having shared these ideas with Dr. Firchow, I am interested in studying her work further to develop a comprehensive theoretical basis for said practice.

Women Empowerment

Ghana's iconic Nima community is an energetic, close-knit community that looks more like one beautiful, large, family than a small township. The women in the community are extremely hardworking, largely responsible for making the Nima market the vibrant place it is. But there’s also a good number of struggling families in the community.

On account of that, I led fundraising for a program organised in collaboration with the Ghana National Commission on Culture to train women from Nima to make beautiful traditional batik, beads, necklaces, and earrings, thus empowering them with skills with which they could start small businesses to support themselves and their families. Twenty women were trained.

Mentorship

Jacques Calvet, the French business executive, says “Experience is a wonderful thing, but not a useful one. When you are young, you do not trust others’ experience—for if you do, this can paralyse you. When you get old, it is too late to use it —and you cannot transmit it for the reasons outlined.” Yet, some experience has to be productively communicated effectively, without alarmism, dictatorship, apprehension, or condescension.

Through this initiative, our team spent some quality time with students at Galaxy International School, interacting with students on the subject of college applications, the college experience, engaging properly with college friends, professors, student organisations, and volunteering opportunities, synthesising the essence of diverse cultures and perspectives, experimenting with ideas, and long-term career prospects.

I selected Galaxy because through Robert Newton, head of ooverse's research team in Ghana, I had developed a special relationship with the school. To an extent, I could relate to the students' backgrounds, international exposure, and collective sense of future possibilities.

Public Health

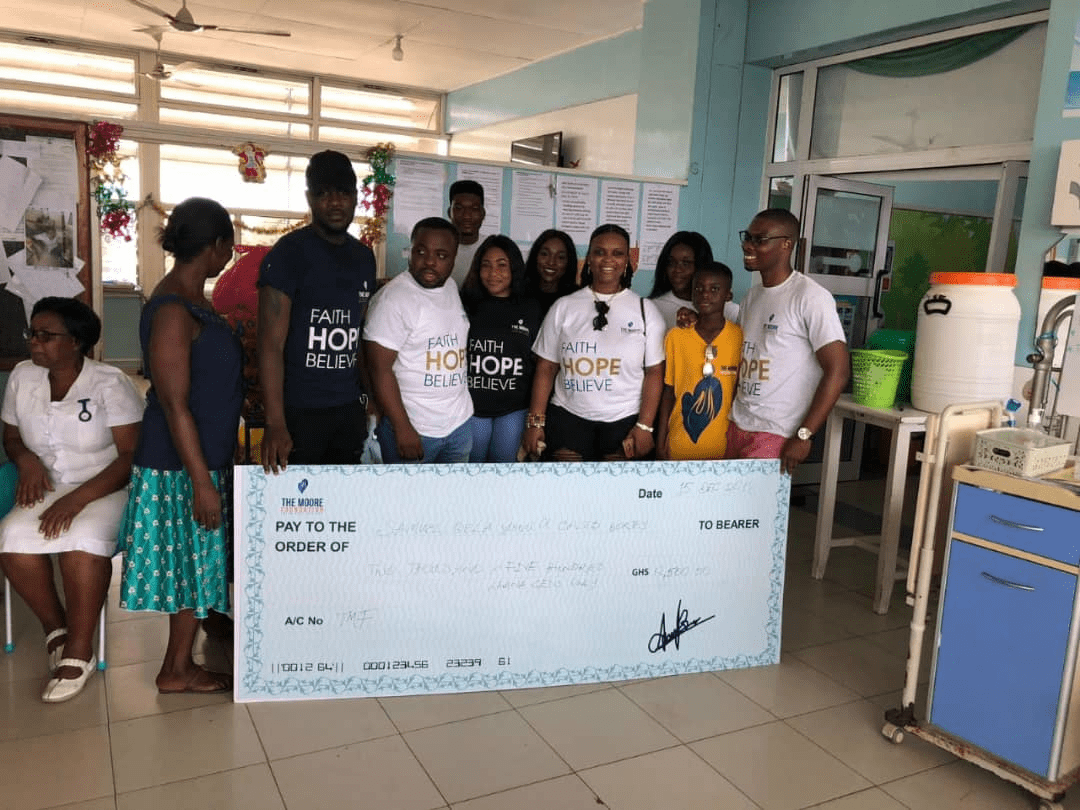

After painfully losing his younger brother to Leukaemia, Patrick Moore opted to translate his grief into inspiration to start a nonprofit to create awareness about Leukaemia in children. The majority of Ghanaians know little to nothing about Leukaemia. This lack of awareness has created a situation whereby the majority of cases end up being too advanced to treat with any success. Another consequence of the lack of awareness, Patrick realised, was a lack of adequate social support for patients and their families. And so with the help of a team of friends volunteering a diverse set of skills, he founded The Moore Foundation.

Under this initiative, I met with Patrick and his team right around this time. Realising that the foundation’s message did not sufficiently communicate its powerful mission to its intended audience, we committed to completely revising the organisation’s website and advising on communication materials. There was particular focus on succinctly communicating what had inspired Patrick to begin this journey in the first place: the fact that a child’s Leukaemia diagnosis can psychologically and financially devastate an entire family. Accordingly, a decision was made that the foundation’s programme and communication materials should spring from that very authentic and emotive place.

Now, The Moore Foundation has successfully organised 8 blood donation drives, 4 Leukemia awareness outreach programmes, 3 donations to the Pediatric Oncology Department and the Haematology Department at the Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, 2 stem cell donor recruitment drives, 1 advocacy walk, 1 charity football gala, and 2 successful fundraisers. It also works with healthcare givers to seek funding for treatment, and partners with DKMS to recruit stem cell donors onto the African registry of The Sunflower Fund. Invited to the organisation's Board of Trustees 3 years ago, I continue to advise on community engagement and the use of tech.

The initiative aims to improve healthcare by promoting due participation in personal and public health. This initiative was founded based on my understanding that health equity is not only an accessibility issue, but also, a participation issue. As in, Jane could live two footsteps away from a free ultra-modern hospital, and still have poor healthcare, if she does not fully participate in her own healthcare; if she remains ignorant about infections, ignores symptoms, avoids medical consultation, fails to stick to prescription and medical advice, or fails to adopt lifestyles compatible with specific risk factors to which she is exposed.

Community Education

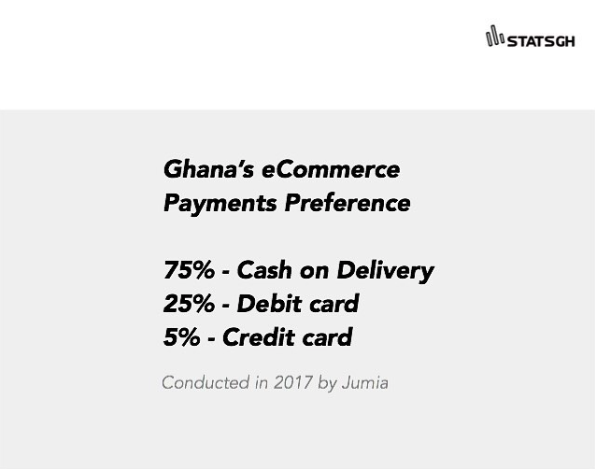

A tendency to turn to data for clarification and enlightenment is a prominent feature in the cultural infrastructure that historically separates developed countries from others. Admittedly, more recently, the shift away from intellectualism and towards a gross disrespect for data is quickly becoming a global theme among ordinary people. However, said culture remains most conspicuous in, and most damaging to, less developed states. I recognise that there is no point democratising data insights if everyday people for whom the access is intended ascribe very little value to data. On this account, this initiative was founded to help create cultures that respect and rely on data.

Stats GH was founded to take statistical figures bandied about in the media and government releases, and relate them to the ordinary person. In an age where people are inundated by content, even educated folk need a little help keeping up to date with important facts. That is why I invested both intellectually and financially in Stats GH.

The audience has grown organically. The founder, Najib Zebrilla, engages quite extensively with the audience, building individual relationships with many followers. Thus, it has been possible to develop considerable insight into the interests and backgrounds of our audience, over time. For example, we know that many followers are Ghanaians in the diaspora who are keenly interested in starting businesses in Ghana. On several occasions, Stats GH has been contracted by individual followers to conduct feasibility studies into business ideas they are contemplating. These contracts have focussed mainly on hospitality, tourism, agriculture, and healthcare, all of which are major contributors to Ghana's economy.

I see huge long-term value in evolving Stats GH into a trusted source of data for small businesses in Ghana, and orient the broader public discourse towards using data and statistics to enlighten rather than bewilder.

The Arts

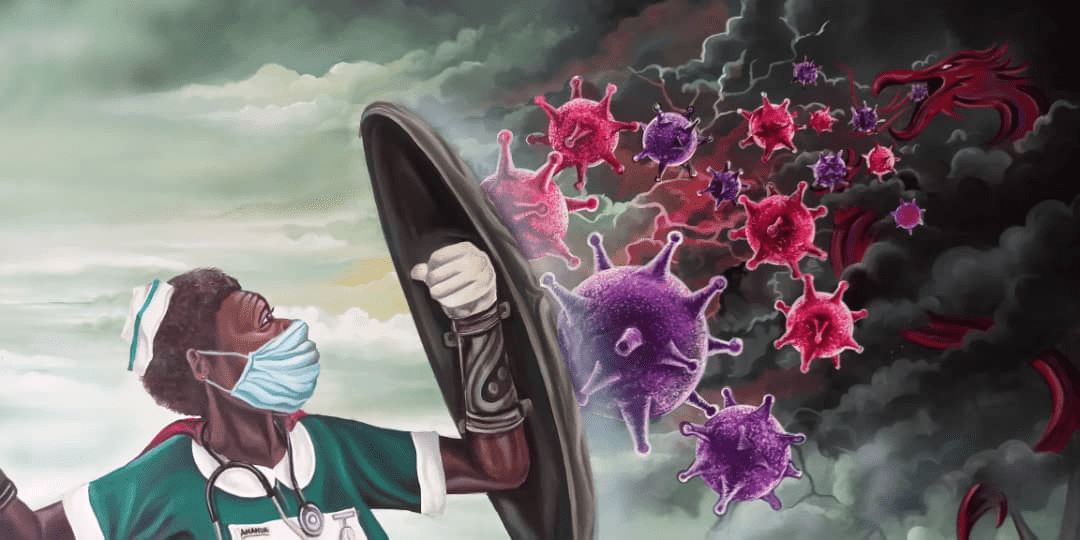

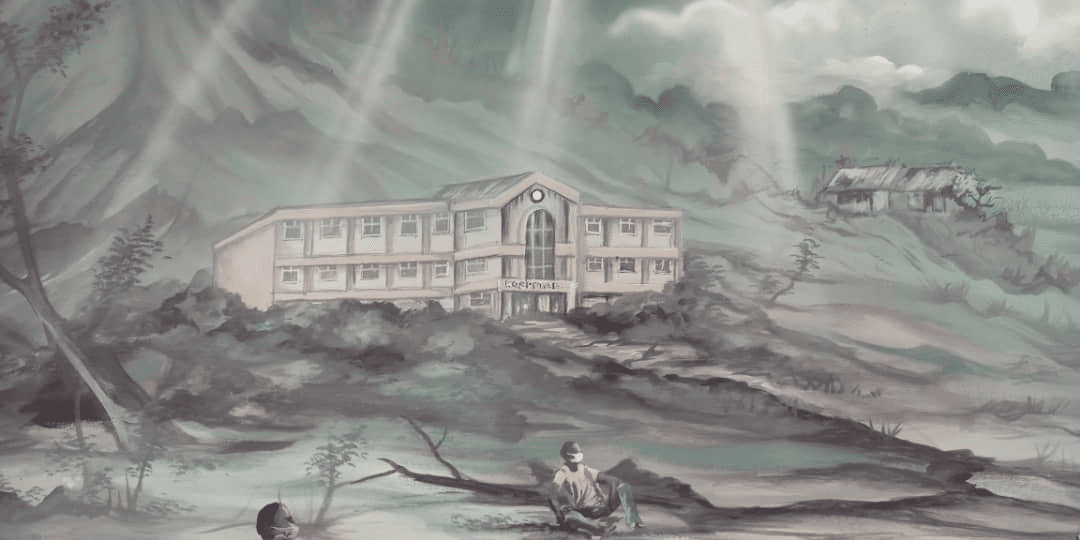

With powerful symbology, we are told two emotive stories concurrently: the story of LIFE unfolding under brighter clouds, on the left, and the story of TRAGEDY unfolding under darker clouds, on the right, whence particles of the novel Coronavirus have been spat out by an emblematic dragon, (signifying the origin of Covid-19). As we follow the frightening streaming particles, we meet a health worker facing the danger head-on! Armed with a sword (symbolising modern science and tech), she gallantly cuts a virus particle into two, behind her. But rather than rest on her little victory, she still holds up her shield (also symbolic of modern science and tech) to ward off further particles of the virus, (which represents possible secondary waves of Covid-19 outbreaks, as well as potential epidemics in the future, indicated by differently-colored virus particles). Dressed in her working outfit, with a stethoscope around her neck, a breast watch, and her name tag, AMANUA, she stands on a rock, which represents the solid backing of government, W.H.O., private institutions, charitable persons, and a generally supportive population.

In mid-ground, we see two doctors in protective garb face masks, devotedly attending to an infected person. From a distant hospital, an ambulance approaches. People, young and old, sit nervously, in nose masks, keeping hand sanitisers close, but keeping a distance from one another. Far less armed to defend themselves, they are undoubtedly dependent on the skill, commitment, and perseverance of our heroine. Up on the hills is an isolated house around which no one is visible, (symbolic of a lockdown). A little boy, feeling intense fear, loss, and helplessness, cries out, without a face mask. We see the Adinkra Symbol, “Gye Nyame” (which means “Except God”), on the sword, symbolising the gravity of the disaster. Below is a graveyard with dead creepy trees, representing the millions of lives lost or otherwise impacted by the pandemic, and the overall decimation of economies worldwide. If one doubts, as some have, that this pandemic is real, one can readily look down to spot the skull on the ground.

In the horror scene we are in, we manage to lift our eyes above the hospital on the hill, to observe bright sunrays, representing hope; hope which is further revealed by leaves that yet remain on partially-withered trees, and a pond of water that still shimmers. Water, we know, is life. It is that hope and that life our God-sent warrior-nurse is protecting, at the frontlines of this terror, at great risk to herself.

On the cape of our brave superhero is a world map with a visible African continent, emphasising the global impact of the pandemic, the Afrocentric nature of this masterpiece, and Ghana’s historic significance as Gateway to Africa. Clearly, our world thrives because of AMANUA’s courage and sacrifice. In reverence to her sacrifice, we are invited to follow two simple rules: firstly, one does not stand on the right of AMANUA’s shield, and secondly, one stands upright to pose in front of the painting. Flouting either rule may expose us to the dragon’s infectious spittle, thus placing us at risk, and belittling AMANUA’s heroism.

The 72-by-108-inch painting which is being displayed at the Ghana National Museum is a poetic love letter to health workers for the incredible professionalism and selflessness they have shown and continue to show through this pandemic. “AMANUA” is our everyday health worker. From loud applauses on balconies in Spain, those heard in the lonely streets of Italy, and promises to increase allowances in Ghana, it is evident that no few words exist to capture the depth of the world’s gratitude. That is why Mr. Hilton, the sublime Ghanaian artist and art director, and I collaborated to create a picture that is worth a billion words. Hilton worked on set construction on the critally acclaimed Netflix series, Sense8. I am proud to have helped to define the striking features and unique rules of the iconic work of art.Field Support

Organisations are often eager to embark on important charitable projects in foreign communities. In some cases, they have the workforce and funding to do so. However, results of the probably expensive intervention often wastes away due to lack of follow-up to ensure that the project takes root and flourishes. Meanwhile, the organisation typically moves on to a new project elsewhere, adding to its portfolio of “successful projects”; a total impact of zero. By providing some follow-up support to organisations that undertake charitable projects in foreign communities, community service is encouraged, outreach projects can meet strategic objectives, and trust can be built with locals to ensure success of future interventions.

Applying these observations to Paanor, a team, led by Dr. Tracy Fams-Okine, sought to really engage with the community on specific issues relating to the outreach. One memorable issue it focussed on was the case of a little girl reported to have dropped out of school because she was being teased incessantly. With the help of Mr. Asiedu, the school’s headmaster, Tracy, with Yvonne, an auditor based in Luxembourg, located the particular girl in the village. The two brilliant and accomplished young women spent a considerable amount of time talking to the little girl, and sharing their personal stories. It did not end there, of course, as the outreach was followed by countless calls, ensuring that the girl indeed returned to school and stayed in school.

There was a consensus among all volunteers that if the only outcome of the outreach was providing that girl with the confidence and inspiration, our outreach in Paanor would be worth it. I believe that the world would be significantly better if half of the world's community outreach programmes delivered on just 1% of their mission.